Project-Based Learning: Giving Choice Within Curricular Boundaries

Maguie Alexander, a secondary school Dominican history teacher, is passionate about the subject she teaches, but realizes students don’t always feel the same way. in order to change that, she decided to explore project-based learning.

An important part of the 8th grade curriculum is the study of the era of Rafael Trujillo, a dictator who wielded power in the Dominican Republic from 1930 to 1961. This is a fascinating study that most of our students can relate to, since their families all have personal stories to tell about their experiences during the dictatorship.

Still, in spite of that, Maguie felt that in the past students didn’t connect with the theme as strongly as she’d like them to. She hoped that project based learning (PBL) — with its focus on teaching through real-world projects and giving learners choice — would make this part of our curriculum feel more relevant to her students.

How the project evolved

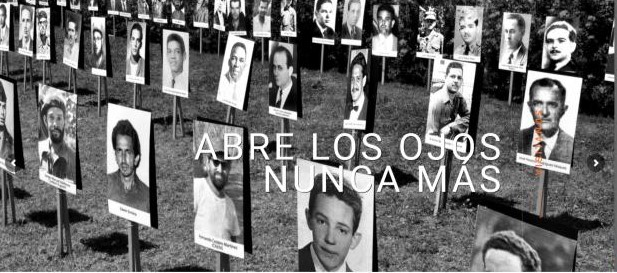

Maguie began the project by stimulating student interest. She started by having students visit the virtual Museo Memorial de la Resistencia, a museum about the Dominican resistance. (Normally, the students would have taken a trip to visit the museum in person, but due to Covid it was not receiving visitors.) Then she had students formulate questions to ask family members about that time period, especially grandparents or older friends of the family.

Students were fascinated by the stories their families had to tell about what it was like to live in fear under a dictatorship and the lack of trust people felt, sometimes even towards their own family members. They discovered that there were a wide range of opinions, from resistance fighters to supporters of the dictatorship. They had a round table discussion to talk about everything they learned, and then Maguie told them that they would be free to study any aspect of Trujillo’s dictatorship that interested them.

Project-based learning is all about choice

1. Choice in the research question

The choice in deciding what they wanted to study made this project personally meaningful to the students. They were asked, “What do you want to investigate? What is your question?”

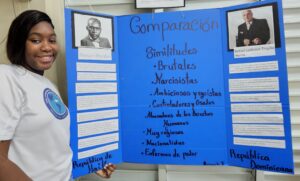

One of the first lessons Maguie taught was how to formulate strong questions which would guide their research. Using the question formulation technique from the Right Question Institute, she showed them the difference between open-ended and closed questions, guiding them to ask open-ended questions that would lead to deeper research. For instance, one of Maguie’s students is a Haitian girl who recently moved to the Dominican Republic. She chose to compare the Haitian dictator “Papa Doc” (1957-1971) with Rafael Trujillo. Another group of students wanted to analyze the different reactions parts of society had to the dictatorship. Others were interested in how Trujillo used tactics of fear to control the country.

Maguie told students that they also had the choice of working in small groups or individually and they could choose who they would work with. However, she also explained that sometimes our close friends don’t make our best work partners. In spite of her warning, some students decided to form groups that didn’t seem optimal for productivity, but she decided to let them try. She felt that even if they weren’t successful, the experience would help them learn an important life lesson that would serve them in the future.

2. Choice through personal learning targets

Before the project began, Maguie created overarching learning goals for her students:

- To identify reliable information

- To understand the causes and consequences of a dictatorship

- To create timelines of historical events.

- To creatively present the information they found

Since students had a wide open choice in the questions that would lead their investigation, Maguie asked her students to create their own learning targets to guide them and which would be used to evaluate their work. They came up with targets like:

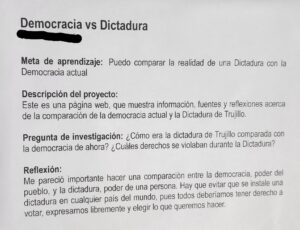

- “I can analyze data and events to support a diagnosis about the psychological state of a dictator.”

- “I can compare the realities of a dictatorship with the democracy of today.”

- “I can explain the effects an event has on different aspects of a country.”

- “I can analyze the role of women and their rights during a dictatorship.”

3. Choice in final product and time management

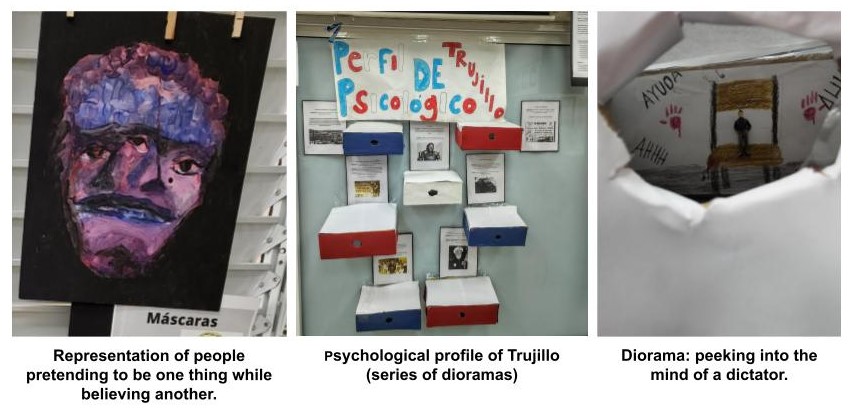

At first, Maguie said it was tempting to give students a list of different formats they could choose from in creating their final product. But she decided that, although this might help her feel more comfortable because she’d have a bit more control, giving wide open choices would allow students to express themselves creatively. In the end, she said, “I’m so glad I did. They went far beyond my expectations for them.”

Students’ creations ranged from handmade artifacts like a graveyard of tombstones representing those who were killed in the dictatorship to digital presentations and websites.

Maguie realized that in giving her students choice, she also needed to give them freedom in the way they used their time. After creating their learning targets, groups came up with a list of steps they would take to do their projects. Every group worked at their own rhythm, and in reflecting on the project, students all mentioned that they liked the fact that they didn’t feel pressured to keep pace with their classmates.

Maguie said, “I tried to respect their use of time, even though it was hard for me at first. I had a hard time letting go of control and trusting them to do their work. But I realized that the final ‘perfect’ product isn’t what’s important — what’s important is giving students the freedom to work the way they want to, to learn from their mistakes, and to go as far as they want in their study.”

4. Choice in how to exhibit their work

As students were wrapping up their projects, they had to decide how they would present their work. Because they had such a variety of artifacts, murals and websites to present, and feeling inspired by the museum they had visited, they decided to create their own museum.

Time was running out and the end of the school year was upon them, so students quickly put the final touches on their work before inviting parents and other classes in to visit. “There was no time to rehearse, which made me nervous,” Maguie said. “But once again, I had to trust my students. When I saw them talking about their work and their learning, I couldn’t have felt more proud of them. All of them spoke well, and they looked so relaxed because they truly knew their information.”

Time was running out and the end of the school year was upon them, so students quickly put the final touches on their work before inviting parents and other classes in to visit. “There was no time to rehearse, which made me nervous,” Maguie said. “But once again, I had to trust my students. When I saw them talking about their work and their learning, I couldn’t have felt more proud of them. All of them spoke well, and they looked so relaxed because they truly knew their information.”

Reflection

Through this PBL experience, Maguie says she learned so many things:

- To trust the kids more. “I learned that sometimes I don’t think students will be able to do something but if I give them the chance they can do more than I expect.”

- To be more flexible. “Not everything has to be perfect and everyone can learn in the way that works for them.”

- To give real choice. “Even if you have to work within restricted parameters, like the curriculum, you can give choices. I was happy to see how students connected analysis to art and creation. Communicating their learning creatively and artistically gave them deep personal expression.”

- To work as a guide on the side. “I had to ask myself — what am I actually here for? I came to a true understanding that my job is not to lead them in their learning, but to support my students as they take control of their own learning.”

Leave a comment