Teaching Independence With Project-Based Learning

Our 6th grade Language Arts (LA) teacher, Christina Perez, had always known that moving to 7th grade — and thus, the beginning of secondary school — was difficult for our students. But this year, when she herself began to teach 7th grade LA, she saw first-hand how stressful this change can be. Things were made even worse by a year and a half of remote learning, since her “babies” hadn’t yet developed the social skills they’d need to navigate a world in which:

- Students go from an ungraded system in our elementary school to one where they receive number grades for the first time. Christina said, “The word ‘fail’ never shows up in elementary — students are always transitioning. But in high school, the number grade means something and they begin to compare grades with one another.”

- Students who were once the oldest in a group (for instance during lunch at the cafeteria) are suddenly the youngest.

- Students have to deal with changes, such as moving from classroom to classroom and working with several teachers, all while riding the rollercoaster of adolescent emotions.

After a difficult year of readjusting to face-to-face learning, Christina wanted her students to finish the school year feeling engaged and successful. She also felt that they depended too much on her guidance and she wanted them to become more independent, taking responsibility for their own learning. Although she had never tried project based learning (PBL) before, she knew that it was an approach that could motivates students by teaching through real-world projects that felt relevant to them. So she decided to join our PBL professional development group at school and give it a try.

While checking out the web site, PBLWork, she came across a project idea that she felt would be perfect for her students: creating a guidebook for students as they transition from 6th grade to 7th grade.

How the project evolved

Christina presented the idea of writing a manual for the incoming 7th graders to her students, but at first they were nervous about it. Did they know enough to write a guidebook? She spent some time reflecting with them about how they felt at the beginning of the year and how they felt now. As they talked about their own experiences, they began to realize how much they had changed and grown and they decided they were ready to share.

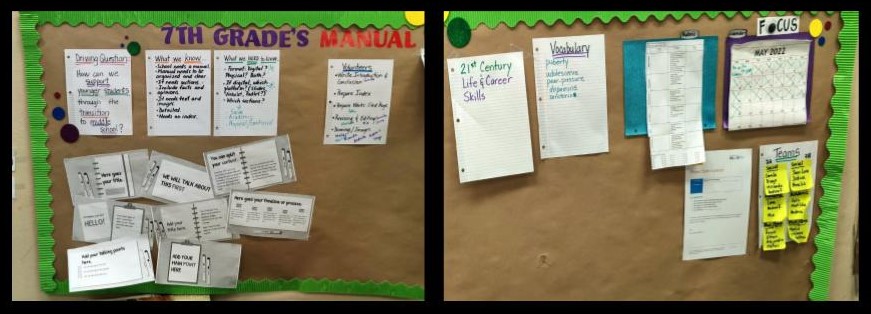

Before they started the project, Christina created a space on her wall where she could post all of the materials students would need (including a team contract, rubric, and success criteria) and where students could easily collect ideas. She included a calendar with checkpoints to help students develop the time management skills that would be a focus of the project.

1. Setting learning goals

Christina’s overarching goal was to teach her students to be more independent. She decided that she would step back and see what they could do on their own with very little scaffolding on her part. She knew some of them would struggle and might not reach their objectives, but she hoped they would grow from this experience. As she planned her unit, these were the skills she wanted students to develop throughout the project:

- To work independently with no teacher guidance.

- Time management is a difficult skill to master, but it’s essential if we want students to be independent learners. To help them monitor their time, Christina had the class create a work calendar with checkpoints.

- Clear success criteria would help students work effectively on their own. Since Christina wanted students to be in charge of the learning, she and her students co-constructed the assessment rubric. This not only gave “buy in” to her students, but thinking through the success criteria developed a clearer understanding of the expectations.

- Collaboration skills would also be necessary if students were to work productively together. Before beginning the work, Christina had them describe how a collaborative group of students work (what would we see? What would we hear?) Based on these ideas students developed a contract about how they were going to work together.

- To develop research skills using primary sources and works cited.

- To improve expository writing skills.

- To enhance presentation skills: instead of simply reading the manuals out loud, the 7th graders were expected to have a conversation with the 6th graders, sharing their experiences.

After walking the student through these goals the actual project work began.

2. Giving students voice and choice

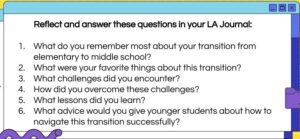

To kick off the project Christina asked her students to journal about their own experiences as they moved to 7th grade. By giving her students time to think, Christina allowed them to explore and develop their ideas, so that when it came time to share, more voices would be heard.

Then, as a group, the class shared their ideas and began brainstorming the common challenges students face when they enter high school. During the brainstorming session, all ideas were accepted without judgment.

Once students had listed all the challenges they could think of, they organized the ideas and divided them into the themes they felt they needed to cover: academic, social, emotional, and physical challenges. Then Christina asked the students to choose the topics that most interested them, having students form groups to cover different themes.

3. Empowering students to take responsibility

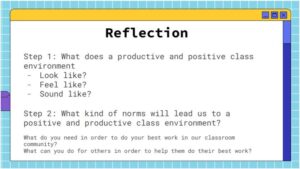

Together, the class came up with a “team contract” setting the expectations for how they would work together. They started by individually reflecting on what a productive class environment would look like, sound like, and feel like. Then, in small groups, they created class norms on chart paper. Finally, as a whole class, they created their team contract.

As students worked on their projects, Christina watched to see how they collaborated. Were they all involved in brainstorming sessions or did one person take over? Could they delegate tasks and support each other? At times she would meet with groups, ask them to reflect on how they were working as a team and, if necessary, how they could improve.

Although collaboration was important as groups worked together on their guidebook, Christina told them that individual responsibility would also be a priority. Students would need to choose a section to write about and they would only be responsible for their individual section. They would each be assessed against the rubric individually, rather than be given a group grade.

Often, when students work in groups, the high achievers feel anxious when their peers don’t pull their weight. This can mean that one or two of the students do the majority of the work. Christina was clear: if one person didn’t complete their part of the work, the others would not be held accountable for it. They would only be graded on their portion of the guidebook. As I interviewed students during the process, many of them mentioned that this was an incredible relief.

4. Putting students in control or their learning through self-advocacy skills

Research made up a large part of the project. Christina wanted students to hear from a professional, so she invited our high school psychologist in to give a workshop on adolescence. She also shared books about the physical and emotional changes that happen in middle school, and students did research on the internet.

Aside from the external research the students did, much of the information they gathered came either from stories of their own struggles or from interviewing high school students about their experiences. Students tried sending out Google Forms to collect information from older students, but found that one-on-one interviews were far better and they liked having the opportunity to interact with their older peers.

It’s not always easy for students to learn how to find, understand, and apply information. Students would need to practice their self-advocacy skills in order to be successful. They would need to decide where to find information and who to reach out to for help when they needed it. To help them in this area, rather than simply providing them with answers when they faced a challenge, Christina constantly used guiding questions to push their thinking, such as:

- “Who could you ask for help?”

- “What words do you find hard to understand?”

- “Where else could you look for information?”

5. Honing presentation skills

The 7th grade classes presented their guide in two sessions to the 6th graders. In the first presentation, they sat at the front of the class, projecting the pages of their manuals to the 6th grade students. This turned out to be awkward and uncomfortable. The idea was to have a conversation about the 6th graders’ fears for the new year and how they could thrive in 7th grade. In actual fact, there were lots of uncomfortable silences punctuated by giggling.

When reflecting on the experience, the students said they didn’t like sitting in front of the class talking. They said they would prefer to answer questions from the 6th graders instead. So changes were made to the presentation process.

The second presentation went much better. Tables were set up for small groups of students with Chromebooks where they could explore the guidebooks. At the beginning of the session, the 6th graders looked through the manuals on the laptops and brainstormed questions they had for the 7th graders. In this more relaxed environment, everyone felt more comfortable. The 6th graders began asking questions and a conversation happened.

Christina’s reflection

What went well

Christina felt that both she and her students learned through this project. She said, “I had to learn to let go, and I did! It was hard because there were times when I wanted to rescue students who were struggling with procrastination, but I felt that more learning would happen if I let them solve their problems on their own. The world wouldn’t come to an end if a few pages in the manual were incomplete.”

For most of the students, it was also a very positive experience. Christina smiles and says, “They owned it!” The students stepped up and did a great job working independently, giving Christina space to conference with students on the project or on other assignments. The two groups of 7th grade students had the opportunity to work with each other, which they liked. They also enjoyed the freedom of going around the school to interview students in other grade levels.

What she’d improve next time

Christina felt that she could have supported students a bit more in the process of researching. She gave her students books with information, but she reflected that next time she would also curate some websites for them. Although she wanted them to research independently, the information online is still too overwhelming for twelve and thirteen year olds to navigate on their own.

If she were to do this project again, Christina says the presentation portion could still do with some tweaking to support a more natural conversation between the 6th and 7th grade students. It was an eye-opener to see that it was so much harder for the students to present to their 6th grade peers than it was to present to their parents.

Would Christina dive into PBL again?

“Definitely! Just to see how students grow more independent and become owners of their project makes it all worth while.”

Leave a comment