The Flipped Feedback Experiment

I love teaching writing, and I think one of the most important things educators can do is give strong feedback to their students. Recently, however, I was feeling increasingly annoyed by the fact that I was spending so much of my personal time perusing student work and writing comments. I was already conferring with students while they wrote, but whenever they handed in drafts, I took them home to give in-depth feedback. I would hand these back during the next class, only to find that students often didn’t really understand my comments. For instance, I made sure to point out strengths in their work along with suggestions for improvement, only to hear them say, “What do you mean, I didn’t revise enough?I didn’t think I had to. Look… you said it was good.”

Agh! I knew I needed to make changes, but I wasn’t sure how.

I had my aha! moment when I read a blog post by Aaron Blackwelder (an English teacher and co-founder of Teachers Going Gradeless) called How to Value Personal Time While Providing Great Feedback. Aaron wrote about not just holding conferences while students are writing their pieces, but actually doing the final grading with them, instead of doing the grading in isolation. This made so much sense to me — it was one of those, “Why didn’t I think of that?” moments, and I immediately began restructuring my classes to make it possible.

My class schedule looks like this:

- Classes are 70 minute blocks that take place 4 days a week

- Two days focus on reading, two days focus on writing

- Class starts with a student-led “word of the day,” followed by a mini-lesson or read-aloud for 15 – 20 minutes

- That’s followed by an activity (quiz, grammar exercise), class discussion, silent reading, or writing

The first problem I faced was how to squash in enough time to actually confer with each of the students. I realized that I would need to flip my classes, starting with the teacher-led mini-lessons, followed by the student-led portion of the class, in order to have enough time to meet with everyone. I would also have to give up control of my class, and have faith that my students would work independently without my supervision. And finally, many of my students have the habit of straggling in late and if I were to wait for them (as I tend to do) about 5 to 10 minutes of class time would be eaten up, so I would have to begin punctually.

With this in mind, I made a few small changes and created my new schedule:

- Mini-lesson or read-aloud and discussion (teacher-led)

- Word of the day (student-led)

- Activity options (independent work)

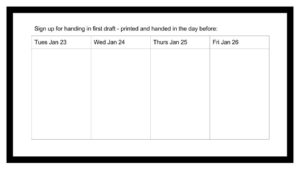

I talked to students about the new way we would be working. The first week, we would start writing with short conferences, as usual. The second week, their first drafts would be due and they could choose which day they’d like to have a conference. Instead of taking their work home to read, I’d meet with them and grade it with them.

I talked to students about the new way we would be working. The first week, we would start writing with short conferences, as usual. The second week, their first drafts would be due and they could choose which day they’d like to have a conference. Instead of taking their work home to read, I’d meet with them and grade it with them.

I expected setting up the schedule to be difficult, but miraculously, it wasn’t. Some students preferred to finish their stories early and signed up for Monday, while others chose later days. They each had their reasons — they organized their due dates according to their extra-curricular activities and, except for a few students, everyone got their first choice.

After the first round of conferences, the second draft would be due two weeks later and — if a further draft was necessary — the last draft would be due a week after that, on the same day they had already chosen. They were to share their draft with me the day before their conference, so that I could read through them before our meeting.

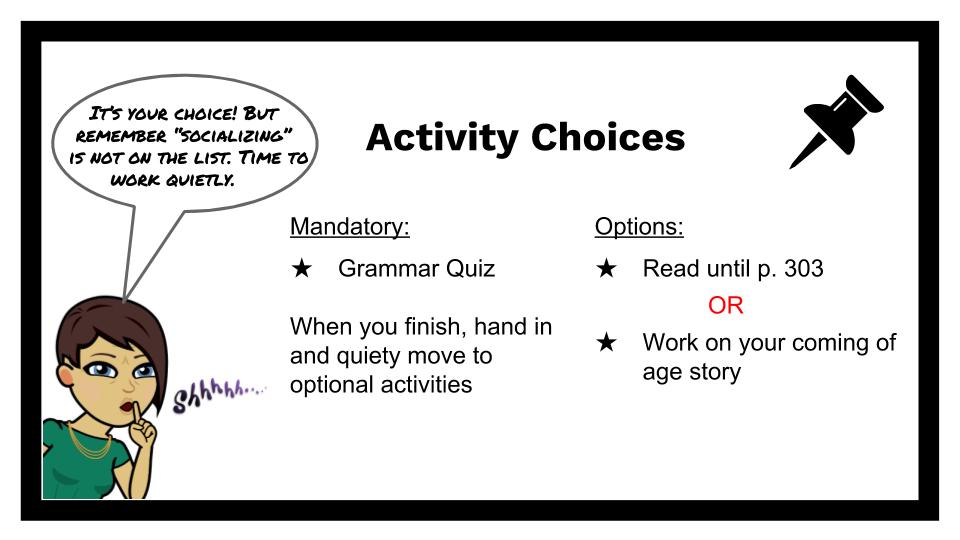

I explained that in order to give me time to meet with them, the mini-lesson would begin promptly. I wouldn’t wait for late students. If they came in late, they were to sit down quietly and find out from their classmates what they’d missed. Then the person in charge of our word of the day would lead the class while I began conferencing. After the word of the day, the student would be in charge of the class. S/he would project the activity choices, hand out any quizzes or photocopies students needed, and everyone would work quietly.

After giving a mini-lesson, the students presented their word of the day, working independently from that moment on, while I began conferencing. My meetings usually started with a few questions:

- What’s the most significant part of your story?

- What’s the message you’re trying to convey here?

- Let me read this paragraph out loud. How could you improve it?

- Listen to this sentence… it’s powerful. What makes it so strong? How could you do more of this?

Once we’d looked at some strengths and weaknesses, I asked them what they felt was the next step they needed to take in order to improve. In most cases, they were able to give themselves the feedback they needed. I simply had to say something like, “Yes, I agree. Expanding on that scene by adding dialogue and some imagery would make it much stronger.”

After going through their piece, I brought out a copy of the 6 traits rubric and walked them through self-assessing for content, organization, sentence structure, word choice, voice, and conventions. Most of them were very clear on their areas of strength and weakness. However, a couple of students wanted to give themselves a 5/5 on everything, even though they clearly identified that they still had a lot of work to do. Since they knew the grades didn’t count, I realized they weren’t doing this to get a better final grade and I was perplexed. However, in talking with them, I finally understood that they were simply weak in self-assessment, and I needed to work with them to help them see their work more objectively. Being able to clearly self-assess is hugely important if we want our students to be able work independently, so I felt that taking the time for this was important.

“Hmm, so you’d give yourself a perfect score for content even though you feel that you haven’t developed your character and you still need to work on showing not telling? Why is that?”

Both of them said something along the lines of: “Well, I worked really hard on this, so I think I deserve a high score.” This led to a great discussion on why hard work doesn’t always translate into a strong draft. When they finally gave themselves a more realistic score, they decided that they needed to put some serious work into revision.

I couldn’t be happier with the results of this experiment. I’m paper-free this weekend, having graded all the stories in class. Students have started coming to class on time and are working independently — and they love the conferences. Most of them said, “Can we do this again? I learned so much. I know exactly what I need to work on.” Because they were the ones critiquing themselves, and I was able to give a lot of praise, all of them left the conference feeling like capable writers and inspired to revise. Best of all? My inbox is full of messages from students saying things like, “Carla, can I meet with you on Monday? I’ve been revising my story and I want you to see how it’s improved.”

Those messages sound motivated and positive. They warm my teacher heart.

For a look at the impact that flipping my feedback had on student growth, check out my blog post on Teachers Going Gradeless.

Relationship is the most powerful tool teachers have. Thanks for trying this strategy and sharing your thoughts.

Thanks for inspiring me Aaron. My students are so much more motivated to write!

I love the reflection evident in this post and seeing how it wasn’t a complete revamping of the class that was needed to achieve the desired results! Little tweaks here and there (and giving up control) did the trick. I love it! Now my mind is going on how this might apply to professional development or adult education on my role…would love to hear any thoughts you have!

Yes, it’s amazing how powerful a small change can be. Hmmm, I like your question about applying this to PD. My first thought is that the main thing is giving up control by letting teachers decide where they need to make improvements and how they’d like to do it. Rather than “evaluating” teachers I think our role is to act as a soundingboard, asking questions to push their thinking, just the way we do in student conferences. I’m sure there are more connections. Let’s share ideas!

Awesome and really inspiring. 🙂

It amazes me that such a small change can make such a big difference!

I love how clearly you explained your process. I too find that students want to give themselves high marks but did not consider helping them become better at self-assessment. How wonderful that you have a system that builds students’ writing, self-assessment and independence and leaves you with less paper at home!

I’m excited about it – it seems to be positive on so many levels. I’m hoping it will help my teachers manage the workload a little better!

Indeed! An approach that supports getting to really know your students too. You are unstoppable Carla! Another post I will share with my heavy-feedback teacher friends.

Thanks for sharing Gillian. Please let me know if they try it and if it works for them. I’d love the feedback!

This sounds great! I was wondering, how many students do you have in each class?

14 in each 11th grade class and 23 in 12th grade. I can hold about 5 of these longer conferences in a class period. Aaron Blackwelder has 130 students in 5 classes.

“When they finally gave themselves a more realistic score, they decided that they needed to put some serious work into revision.”

This is crucial. Kudos for this great work and thanks for sharing!

I loved bumping into your blog and seeing how you continue to push boundaries and experiment with new teaching methods. I was immediatly transported back to 7th grade Writing Workshop and overcome with becautiful memories of haikus and your green pen mark ups. To this day you continue to be the best teacher I have ever had!

Carola, how wonderful to hear from you. Thank you for writing – your comment made my day!! Pop by the school and see us sometime!

Oh my God this is so helpful! for teaching acting as well! Thank you!

Any time little sister!