Scaffolding Literary Analysis: Step-by-Step to Reach Success

Let’s face it — for most students, literary analysis is just plain hard.

And teaching it is even harder.

All too often, when teachers feel pressured to cover curriculum, they focus on teaching content rather than skills, when in actual fact, skills are what our students will take away from our classrooms. We tend to think that students will somehow develop these abilities (through osmosis?) as we teach our content. But the truth is, most students need explicit teaching of skills, which should be taught through our content.

In other words, content knowledge is not the goal — skills are the goal and content is the medium through which we teach those skills. Reading analysis can be difficult to teach, though, and in order to do it well, we need to break it down into small, manageable chunks which we teach and reteach as often as necessary.

Our Language Arts teachers recently noticed that students were having difficulty answering reading comprehension questions. In 7th grade, for their reading assignments, students were expected to include an opinion, evidence to support their opinion, and an explanation of how that evidence supported their answer. By 12th grade, they needed to include a thesis statement and several paragraphs of evidence, along with analysis of that evidence. At all grade levels students were struggling with these different components, and our teachers decided that they needed to work together to break down the lessons and scaffold the learning until students could work independently.

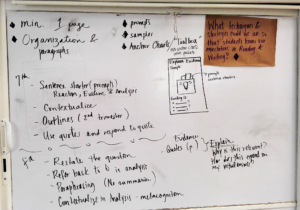

In order to provide step-by-step instructions, it was essential for teachers to have a clear understanding of what had been taught in previous years so that they could build on past lessons, consistently extending students’ learning until they were able to write a s trong literary analysis essay. Our Language Arts teachers met to develop a continuum of skills they should be teaching and to brainstorm techniques that they could use to teach them. They began by identifying their objective: what should students be able to do by the time they graduate high school? Knowing their final goal, they worked backwards, breaking down the tasks into specific skills they would teach at each grade level. After developing the continuum, they began to create lessons that would help students master each step of the process.

trong literary analysis essay. Our Language Arts teachers met to develop a continuum of skills they should be teaching and to brainstorm techniques that they could use to teach them. They began by identifying their objective: what should students be able to do by the time they graduate high school? Knowing their final goal, they worked backwards, breaking down the tasks into specific skills they would teach at each grade level. After developing the continuum, they began to create lessons that would help students master each step of the process.

An example of teaching literary analysis in 8th grade:

In 8th grade, teachers decided that their students should be able to do the following:

- restate the question in their answer

- paraphrase or quote evidence

- make an analysis by referring back to the question, contextualizing, and explaining how their evidence proves their quote

The 8th grade lessons:

- Students were given a reading response assignment and, along with their teacher, they created a rubric to guide them.

- After they wrote their responses, their teacher, Laura, identified the elements that her students found difficult.

-

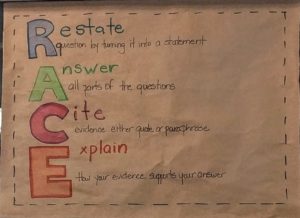

She gave them a mini-lesson on the different parts of a response (R.A.C.E.). The R.A.C.E. criteria are posted on an anchor chart in the classroom. Anchor charts scaffold the learning by allowing students to refer to them whenever they need them.

- Then Laura asked her students to highlight their work with different colors to identify each part of the R.A.C.E. process.

- After color coding, students needed to self-assess their literary analyses by grading themselves on their previously-created rubric.

-

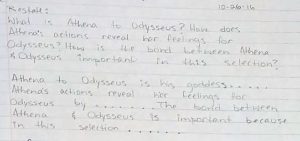

Although they had been taught to restate questions in previous years, most of the students were still having difficulty with this skill. Laura decided to begin each class with an entrance slip in which they practiced restating a question. The entrance slips were not graded, but Laura gave them detailed feedback in order to help them improve.

- In subsequent reading responses, in order to help students learn to independently self-assess and revise their work, students had to highlight their work using the R.A.C.E. criteria. If they noticed that they were missing elements, they were to add them before handing their work in.

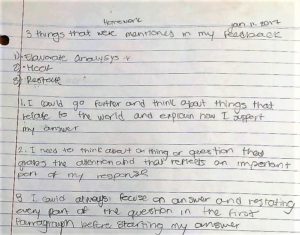

- After the students had worked on several responses, Laura asked her students to look back over all of their feedback, identify three opportunities for improvement, and then rewrite their latest response, trying to progress in the areas they’d identified.

Thanks to Laura’s explicit teaching of skills, most of the 8th grade students are now managing to write cohesive, in-depth analyses of their reading.

Teamwork rocks! It’s by working together that our Language Arts teachers are making such an incredible difference. They’re using this type of scaffolding at each grade level, helping students incorporate new skills. In the 9th grade, students are taught to expand on their responses by including a strong hook in their introduction and by supporting their opinions with two pieces of evidence. Stepping stones are added until, by grade 12, students are comfortable writing a literary analysis paper, fluidly incorporating quotes into their work, and clearly analyzing how the evidence connects to their opinions.

Scaffolding helps students develop a growth mindset — and when they finally master a skill that seemed impossibly difficult at first, they develop self-confidence and begin to take risks. They’re also developing independence: learning to self-assess and revise their work without needing as much feedback from teachers. Although teachers need to put in a lot of time and effort (and have a fair bit of patience!) during the scaffolded lessons, this kind of teaching pays off in the long run. Students are eventually able to work independently, and their assignments are much stronger.

Hi Carla- I enjoyed learning about what 8th grade literary analysis should look like. I often have students to restate their questions and paraphrase but, sometimes second guess what I am asking of my students and worry I am asking too much of them. This post helped me identify where they should be. Thanks for posting such a comprehensive piece.

Thanks for reading Anthony! Our teachers also struggled with the feeling that they’re expectations were too high. Clearly defining what they should expect at each level and then working with the students to make sure they understood the expectations, has made all the difference. Students are feeling successful and confident.

As a former AP literature teacher, I can say that this skill building is essential. Even when they got to me in 11th or 12th grade, I would still need to spend time teaching the nuts and bolts of analysis using various scaffolding methods, TPCASTT. SOAPSTone or DIDDLS, or a few others. The scaffold made it very clear what the student was looking for, and after some handholding and walking through a few of the types, they caught on rather quickly and left the scaffolding behind. You article contains some great tips that I can use with my middle school teachers to help get that skill development started earlier, and to the benefit of our students. Thanks so much!

I’m glad this was helpful to you Tom. We have an amazing group of teachers and they were all working hard to help their students, but they felt frustrated because they didn’t clearly know what was expected at each grade level. Hashing out what students should be able to do at each grade level and to clarify their role in this continuum of learning has helped all of them feel more effective and less frustrated. And our kids are rocking reading responses!

Hi Carla! You write so well. Love your blog posts. This one just shows what is possible when care and imagination come together. I think the strategy is a powerful one and the expectations per grade easily achieved–as you can see. I will share this with my English-teacher friends. #sunchatblogger

Thanks Gillian! Having teacher share their weaknesses and truly collaborate has given incredible results…they’re an inspiring team!