Lessons from Virtual Learning: Teaching Self-Advocacy

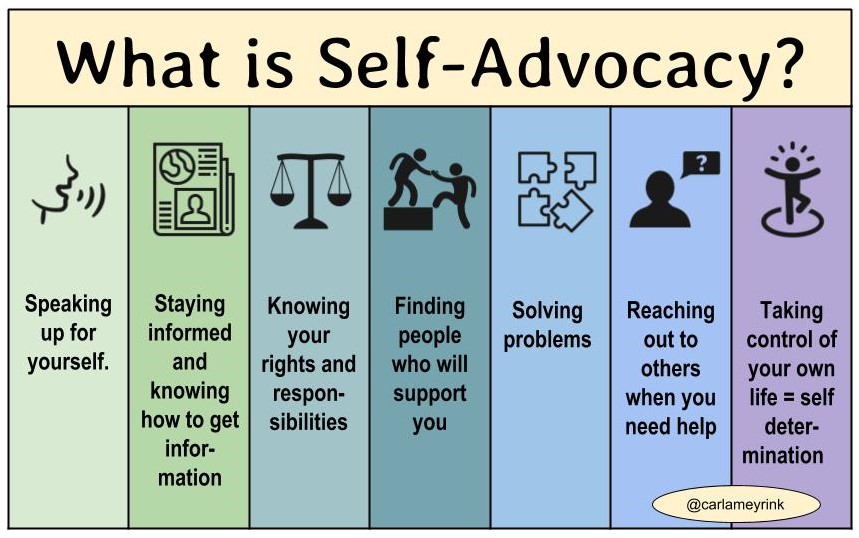

Graphic adapted from: rule-the-school.com

At TCFL, we teach certain self-advocacy skills to our students. Most of them have no problem coming to the office to express a concern or going to their teacher with an issue. They will tell us about anything that bothers them, from having too much homework to wanting to cut down on the use of plastic in the cafeteria.

So, you can imagine my surprise when, recently, I began teaching virtually and realized that the majority of my students were not asking for help when they needed it. In fairness, in a classroom setting, students don’t often have to do this: with a glance around the room, teachers can generally read body language and facial expressions to see who’s struggling. We can walk around and look at students’ work to see who needs help. We can listen in on small group discussions and pick up on misconceptions. But in the virtual classroom, this option disappears — and we become much more dependent on our students’ ability to recognize the need for help and ask for it.

I was frustrated by my inability to reach my students. When I dropped into Zoom Breakout rooms and asked them if I could help with anything, they would tell me they were “fine.” But then I would meet with them one-on-one in a scheduled conference, after they spent two weeks working on a draft, only to hear them say, “I didn’t work on the dialogue because I didn’t know how to make it sound real.”

I decided that this would be the perfect time to start teaching my students how to get the help they need.

The steps I took:

- I started by asking my students what self-advocacy meant to them. Their answers included:

Coming of Age Self-Advocacy Form

- Being able to speak up for yourself .

- Letting people know what you are capable of.

- Having self-confidence.

- I shared the self-advocacy graphic above and we discussed the different points, especially focusing on “reaching out to others for help.”

- We talked about asking for help when they need it and the fact that asking questions is a strength, not a weakness.

- I decided to tell students that I wouldn’t only be assessing their writing in class, I would be assessing their ability show vulnerability and ask questions about their writing.

- I made a Google form for them to fill out. They had to include three questions, explain where they got their answers, and write a reflection on different aspects of asking for help. (Find a copy of my form here.)

- As an example, one question might be, ‘How can I show not tell in this scene?’ and the student may have found their answer by looking online, talking to other students in writing workshop, or shooting me an email.

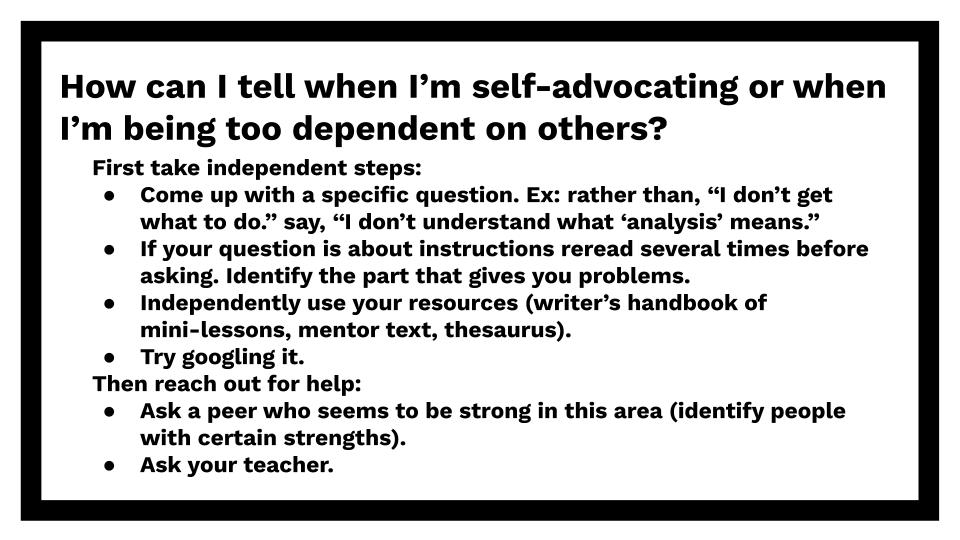

Some of them mentioned that they didn’t always dare to ask questions because they worried that they were too dependent on others. I thought this question was especially important, so we discussed it and came up with answers:

Throughout classes, I constantly reminded them to advocate for themselves and gave positive feedback when I saw it, saying things like:

- “Hey that’s a great question! Thanks for asking. I’m sure others in the group are wondering too.”

- “ I love the way you advocated for yourself. Keep it up.”

The results:

Over the course of the last two weeks, as I worked on this, I saw some important changes in my classroom:

- More students have been asking for conferences.

- Some students are now messaging me in the evenings and on weekends, asking for help – some may see this as a disadvantage, but I’m so happy to see them reaching out!

- Students are coming up with stronger, more precise questions about their work, such as: “How can I incorporate flashbacks/dreams into my story?” and “Where can I add more details to my writing to make my story more impactful?”

- Students realized that in order to come up with questions about their work they needed to put more effort into their drafts. As one student explained, “As soon as I began working I easily came up with questions. I just needed to really concentrate on it because if I worked on it ‘superficially’ rather than really getting into it, I would not have come up with the questions.”

- I’m seeing growth in risk-taking. One student said, “I’ve become better in becoming vulnerable to other people and asking them for help.”

Self-advocacy empowers students as it helps them become independent, life-long learners. The virtual classroom has shown me that I cannot just expect students to pick up these skills naturally. Instead, I need to actively teach students how to ask precise questions, solve their own problems, and reach out for help, by consistently embedding these lessons into my classes.

I love this- this is such an important skill and one we often feel like students just know.